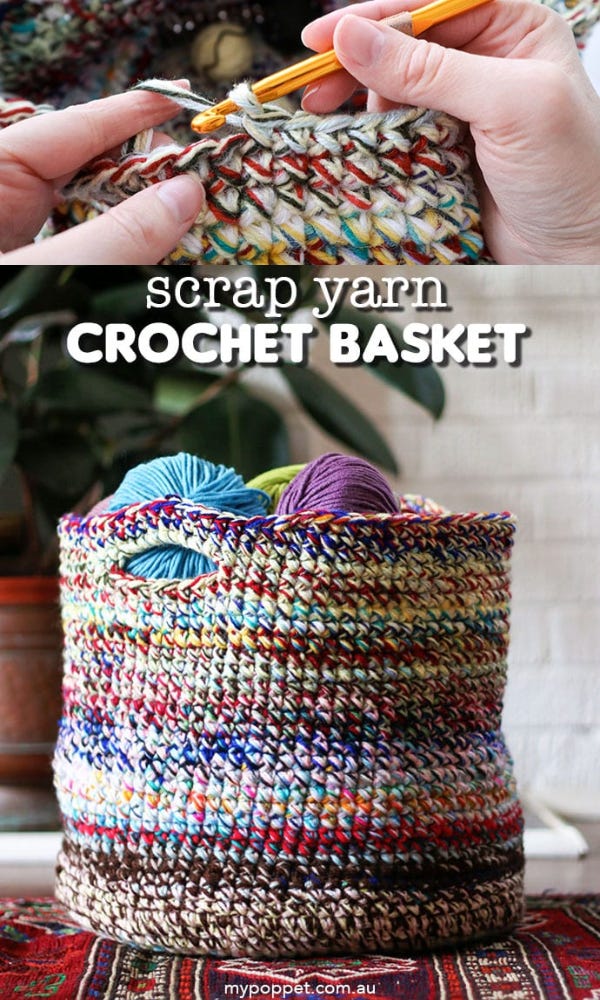

Since Fantasy Machine in October, I’ve been taking a bit of a studio break. I’m working very slowly on a couple things, but have been trying to give myself time to focus on some personal projects instead. Right at this moment, I am sitting on my couch next to a sleeping dog and cat, crocheting a basket out of some t-shirt yarn. Made using this tutorial from Wear, Repair and Repurpose, by Lily Fulop.

I like to keep these side non-studio, non fine art projects going to keep my hands busy while I watch TV or chat with friends, or drink my coffee in the morning. But, like most artists (I think), my brain is always in the studio even if my body is elsewhere, so I have been thinking long and hard about my favorite scrap based works of art. I started the long and laborious process of turning a bunch of old t-shirts into yarn a year or more ago, and they’ve been sitting in a Savers bag in my closet waiting to be used for something-anything! I have a real sentimental attachment to clothing items, and it’s hard for me to get rid of anything. Seeing some of these old things I used to love has got me thinking about the garments themselves, and about scraps as a material.

A Brief Inventory of Formerly Beloved T-Shirts:

An orangey-red T Shirt with Nebraska printed on the front in white Comic Sans, given to me by an artist friend at my first big boy residency

My very favorite, incredibly threadbare gray women’s t shirt from high school, purchased at my first job at 15 and worn at least once a week until 25

Promotional t shirt from my most recent non profit job, incredibly comfy for sleeping, gives me non profit industrial complex induced trauma flashbacks every time I wear it

A striped Target T shirt I stole from an ex boyfriend in 2015 and turned into a crop top

A thrifted Velvet Underground T shirt bought in high school to show off my alt music cred and worn with jeans and Converse for years

Now these old garments have lived a whole lifetime, and are beginning a new one as a functional and pretty little basket for even more scraps, or blankets, or a comfy place for a cat to nap. The t-shirt yarn crochets up in a chunky, somewhat stretchy, extra durable way, and making several balls of it out of about 10 t-shirts took roughly 1 season of Criminal Minds to complete. Thrift stores are full of these cast off garments, especially novelty t-shirts that have been printed up to commemorate a family reunion, or a corporate conference, or a fundraiser 5K you get bullied into participating in by your coworkers’ kids. The majority of these will be rotting in a massive landfill in East Africa by the end of the year, being picked over by local artisans trying their best to make something out of the mountains of textile garbage dropped in their neighborhoods by us overconsumers in the global North.

I’m always suspicious of individual solutions to systemic problems, and any attempt to stop over-consumption in the name of environmental and labor concerns in our capitalist economy is ultimately an individual act, and can only do so much. I’ll admit to throwing away usable textiles in the name of convenience now and again. We’re all only one person, and none of us are perfect. But using up even the tiniest scraps of garments feels like paying respect to the people who labored to grow the cotton, process it, dye it, knit it up into a jersey fabric, and sew the garments into usable items that have brought me a lot of joy. I like to think small acts like reusing and respecting these materials is a way of being in solidarity with these workers who I have little connection to outside of our shared engagement in the global garment supply chain. So often, I have found myself at a shitty job thinking about how I’m wasting away my life for someone else’s profit, or to create an item or provide a service that ultimately serves nobody. I like to think that if I were a garment worker, I would appreciate the effort that goes into keeping the items I worked so hard to produce useful in some way or another.

In domestic textile traditions, using scraps was a matter of practicality, rather than being environmentally motivated. Right after Christmas, my partner and I went to see the show Called to Create: Black Artists of the American South at the National Gallery of Art in DC. It features several of the quilts of Gee’s Bend, which I have seen a few times. My partner got to experience these works for the first time on this visit, and we were both particularly struck by Blocks and Strips Work Clothes Quilt (1942), by Missorui Pettway and her daughter Arlonzia.

Arlonzia describes the quilt like this:

"It was when Daddy died. I was about seventeen, eighteen. He stayed sick about eight months and passed on. Mama say, 'I going to take his work clothes, shape them into a quilt to remember him, and cover up under it for love.' She take his old pants legs and shirttails, take all the clothes he had, just enough to make that quilt, and I helped her tore them up. Bottom of the pants is narrow, top is wide, and she had me to cutting the top part out and to shape them up in even strips."

The beauty of the idea of “covering up under it for love” was enough to bring both my partner and I nearly to tears in the gallery. There’s a whole history, a whole life full of work days, family meals, fights, laughter, and joy wrapped up in those garments, and now in their scraps, and now in that quilt.

Like Missouri Pettway and the other quilters of Gee’s Bend, dykecon and legendary visual artist Harmony Hammond employed scrap fabric in her incredible Floorpiece series. I saw her retrospective, Material Witness: Five Decades of Art at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Connecticut with my mom a few years ago, and had the great privilege of seeing her Floorpieces (I-IV) in one place.

Seeing her Floorpiece compositions in person (and from above! As the artist and god intended) was absolutely incredible. These pieces are based on rag rugs, a proud traditional hailing from New England, like myself. They are sturdy, warm rugs made from braided together scraps of old clothing or home textiles. Harmony takes this very simple material and process and churns out some of the most visually engaging pieces of modern art I’ve ever seen in person.

Missouri Pettway and Harmony Hammond are just two examples of the ways that fiber artists have used scraps in their practices to make emotionally moving and visually arresting works of art. Their ability to create these profound objects out of next to nothing is a reminder of the potential of human labor and creativity. It reminds me that art is ultimately about a primal human urge to make your environment more beautiful, strange, comfortable, or wondrous than it was before you existed.

I’ll be keeping that in mind the rest of this winter, which I will be spending in the studio sorting through my piles of tiny fabric scraps, and attempting to make them into something beautiful.